On a quiet afternoon at Gold Palace jewelers in downtown Bengaluru, shopkeeper Shaik Ameen expressed concern over sluggish trading as Indian families reduce pre-wedding purchases amidst soaring bullion prices.

Before gold prices surged, 29-year-old Ameen, who assists his father in managing the store, noted that roughly half of the daily walk-in customers—around 50 in total—typically made purchases. Now, that figure has dropped to about a quarter.

“People have stopped buying,” lamented Ameen. “Those who could afford 100 or 200 grams before now settle for 50 to 60 grams.”

Gold holds significant cultural value for Indian consumers, traditionally viewed as a secure investment linked to Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth and prosperity.

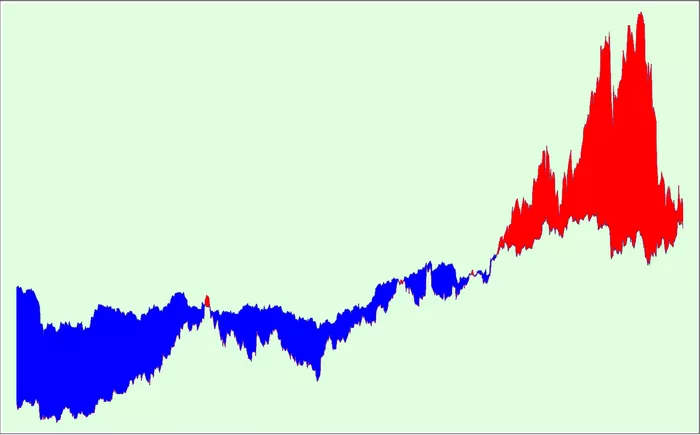

Over the past year, gold prices in rupee terms have risen by 24%, driven by geopolitical tensions in the Middle East and Ukraine, alongside substantial speculative investments from China, now the world’s leading gold importer surpassing India.

Despite its cultural significance in Hindu festivals and weddings, demand for gold jewelry in India declined by 6% last year, according to the World Gold Council, in contrast to a 10% rise in China.

Crisil, an Indian analytics firm owned by S&P Global, anticipates stagnant sales volumes through March 2025.

Titan, the jewelry and fashion arm of Tata Sons, reported a fourth-quarter profit of Rs7.9 billion ($95 million) in May, falling short of analyst expectations due to reduced demand driven by high gold prices.

While India’s affinity for gold remains strong, Surendra Mehta, national secretary of the India Bullion and Jewellers Association, cautioned that escalating costs could impact families preparing for weddings.

“They have two options: either buy smaller quantities or lower purity,” he explained. “I don’t foresee prices correcting in the near future.”

Although Indians often accumulate gold for weddings years in advance, last-minute purchases are sometimes unavoidable.

For Kishita Gupta, a 26-year-old marketing executive in Meerut, a tenth of her wedding budget was allocated to jewelry, some purchased two years earlier. However, faced with soaring prices, she opted for less expensive artificial jewelry closer to her March ceremony.

Societal expectations put pressure on parents due to high gold prices, Gupta noted, prompting adjustments such as mixing old jewelry with new, as mentioned by Mehak Sagar Shahani, founder of WedMeGood.

Rising costs across the wedding industry post-Covid, compounded by high gold prices, have made expenditure less effective, observed Vithika Agarwal, co-founder of Divya Vithika Wedding Planners in Bengaluru.

However, Agarwal noted that the wealthiest clients continue to host lavish celebrations unaffected by economic fluctuations.

“In high-end circles, the display remains paramount,” she remarked. “Certain cultures prioritize the grandeur of events.”

Anant Ambani’s upcoming wedding to Radhika Merchant exemplifies this extravagance, with pre-wedding festivities featuring celebrities and opulent settings at Reliance Industries’ Jamnagar refinery, garnering global attention.

At C Krishniah Chetty Group of Jewellers, a Bengaluru institution frequented by affluent clientele including the Maharaja of Mysore, sales associate Anil Karumbaya dismissed suggestions of reduced spending among the city’s wealthy elite.

“Bengaluru’s Silicon Valley is home to numerous billionaires and millionaires,” Karumbaya emphasized. During a tour of the store’s exclusive collections, he discreetly redirected attention from high-profile customers negotiating purchases.

“The upper and middle classes continue to patronize us,” he affirmed. “The price hasn’t deterred them.”

Karumbaya added that appearances can be deceiving in a city where many residents possess substantial wealth. “People here have money. It’s not uncommon for someone in simple attire to walk out with a $12,000 bill,” he concluded.

Related topics: